![[Dead or Alive - Youthquake]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/DeadorAliveYouthquake19158047_f-300x300.jpg)

I didn’t know what to make of Pete Burns the first time I encountered him in the video for Dead or Alive’s “You Spin Me ‘Round (Like a Record)”.

Boy George and Annie Lennox had already blurred the androgyny lines in the years leading up to Dead or Alive’s debut, but Burns took it a step further. His rough baritone stood in sharp contrast to Boy George’s soulful tenor. He shook his hips and wagged his finger like a woman, but the eye patch and black clothing made you think he could kick your ass in the alley.

If I had been better conditioned to internalize my homophobia, I would have been repulsed by Burns’ feminine wiles. Instead, I would mimic his moves in front of the radio.

He was confusing, and that confusion was fascinating. He was scary and inspiring, no doubt offensive to my Catholic family to whom he would have probably given zero fucks.

I thought about buying Youthquake when it came out, but I wanted to make sure it had at least two other hits before I sank my allowance on it. Dead or Alive would score a second hit in the US with “Brand New Lover” on the following album, Mad, Bad and Dangerous. By then, I had already cycled through urban radio before eventually settling on college rock.

But I made sure to at least own “You Spin Me ‘Round” on 7-inch.

Over the years, I would encounter Pete Burns and shake my head over the transformation in his appearance. In my mind, he was a skilled acrobat on the thin edge of masculine and feminine, but he obviously disagreed.

Despite all the loss in 2016, Burns is the closest to home the Reaper’s scythe had hit. Prince was my brother’s artist, and David Bowie was once-removed in his influence on my life. Burns, however, was one of the first signals that I would not lead the heteronormative life of a first generation Filipino son.

Looking back on it now, he was probably the first public figure to plant the idea in my mind that being queer was not only acceptable but a source of strength. Yeah, you could be a sissy but a sissy who could kick someone’s ass in the alley.

Tags: dead or alive, gay influence, pete burns

![[Duran Duran, 1983] [Duran Duran, 1983]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/duran_duran_us_1983.jpg)

Duran Duran looms pretty large over my life.

A lot of the earliest songs I wrote attempted to rip them off, an influence I made more blatant as my songwriting improved. A good percentage of my music collection consists of recordings by the band and various spin-off projects. As of this writing, I’ve seen them in concert five times in three different states: three times in Texas and one each New York and Washington.

In the early ’90s, I helped to administer Tiger List, one of the earliest fan communities on the Internet. They were partly responsible for the launch of my career as a web developer — one of the first sites I built was a FAQ about the band.

But the underlying drive behind all this fandom was the fact I developed some pretty hard crushes on Simon Le Bon and Roger Taylor in the 7th grade.

That would have been around 1984, when MTV made it a requirement for rock stars to be photogenic. Although my household didn’t subscribe to cable, a number of broadcast options made music videos accessible. One of these shows introduced me to Duran Duran.

Oddly enough, the effect of “Rio” and “New Moon on Monday” wasn’t immediately revelatory — I remember thinking they were fun, but I was more interested in Eurythmics — but they planted seeds when I later encountered “Hungry Like the Wolf” playing on a VCR display at a department store.

That was the clincher.

“The Reflex” was rocketing up the charts as well, making the song inescapable on any number of family drives with the radio blasting. When I finally attached the name “Duran Duran” too all these separate encounters, I sought them out.

Back then, music magazines would publish lyrics to hit songs, and one of them featured a centerfold of Simon Le Bon. He had on his white shirt and dark pants — his attire in the video for “The Reflex” — and held a microphone to his mouth.

He cut a striking figure, and that’s when I felt something a bit more than just admiration.

My attraction to Simon transferred to Roger after acquiring The Book of Words, a fan souvenir book containing lyrics to the band’s songs up to “The Wild Boys”. Oh, and there were plenty of pictures of the band. My copy is quite ragged from having thumbed through it an uncountable number of times.

I didn’t actually attach the word “attraction” to what I felt at the time, but I could sense it would get me in trouble if I didn’t provide cover for it. So I bought the band’s albums, dubbed them to cassette, played them repeatedly on the family boombox and studied them. Yes, my earliest lessons in how to arrange music came from picking apart how Duran Duran songs were put together.

I became an advocate for Duran Duran’s music because I lived in a time when a pre-teen boy wasn’t allowed to express physical attraction to male pop idols. When classmates attacked that choice, I stuck to the artfulness of the music, the album covers, the videos as my defense, but I knew I could talk about who was cutest with the best of the female fans.

But what started out as a cover became a defining influence. Duran Duran taught me it was OK not to learn the blues progression. They encouraged me to find other artists with a sense for adventure, and they demonstrated that art and commerce aren’t mutually exclusive.

That era had any number of pop stars that could have been the catalyst for my sexual awakening — subsequent crushes include Sting, Huey Lewis, Robert Palmer and even Bruce Springsteen — but Duran Duran was the first, and they ended up being much more.

Tags: duran duran, gay influence

“How did you know you were gay?”

No one has really asked me this question, and from what I gather, I’m supposed to turn this question around and ask the (presumably heterosexual) asker, “How did you know you were straight?”

But my answer to the question would be pretty easy to track through the music I was listening to at the cusp of adolescence. It shouldn’t be a surprise that the I gravitated toward bands with handsome singers — your Simon Le Bons, your Huey Lewises, your Stings, your Bruce Springsteens.

I didn’t connect the growing fascination I had for these pop idols with the orientation my sexuality would eventually align because the curriculum of my Catholic education was clear — I was fated to develop an attraction to women because any alternative would be unacceptable.

So I used music as a cover. Yes, I dug the songs, but they weren’t the only draw.

Exhibit A: Sting, “Love is the Seventh Wave”

![[Sting - Love Is the Seventh Wave] [Sting - Love Is the Seventh Wave]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Sting-Love_Is_The_Seventh_Wave_New_Mix-Back--296x300.jpg) The back cover of this single had Sting posing without a shirt, and I couldn’t tear my eyes away. My household toed the homophobic line because my parents were devoutly Catholic and my brother and sisters weren’t old enough to come to their conclusions. So I would sneak peeks at this image surreptitiously, not exploring why I was so powerfully drawn to it.

The back cover of this single had Sting posing without a shirt, and I couldn’t tear my eyes away. My household toed the homophobic line because my parents were devoutly Catholic and my brother and sisters weren’t old enough to come to their conclusions. So I would sneak peeks at this image surreptitiously, not exploring why I was so powerfully drawn to it.

Technically, my brother owned that 7-inch single, and he called dibs on Sting in our Sibling Rivalry Collection Race. My hormones would not be denied, and I wrestled Sting from his monopoly. I dubbed his Sting albums to cassette without his permission, and I played “Russians” at my first piano recital.

The Dream of the Blue Turtles and … Nothing Like the Sun are awesome albums in their own right, but I could count on the music press to include a few pictures of Sting stripped to the waist.

Exhibit B: Midnight Oil, Blue Sky Mining

I didn’t actually like Midnight Oil when a pair of friends subjected me to Diesel and Dust in the car as we drove around town. But I eventually adjusted to Peter Garrett’s warble, and the songcraft of the album won me over.

One of the friends who introduced me to Midnight Oil would be the first person with whom I’d fall in love. I remember one night dropping him off at his house after a night out and driving back, mumbling to myself that I loved him. I can’t remember another time when I felt both solace and burden in a single thought.

Blue Sky Mining followed Diesel and Dust two years later, by which time my feelings for my friend made senior year in high school a slog. I listened to the album day in and day out because I had to escape into something that linked me to him. And I could use my growing interest in college rock as another cover.

Exhibit C: R.E.M., “Country Feedback”

My friend went to the Mainland for college, and I stayed in Honolulu. During my first semester, I would play Out of Time by R.E.M. every morning, and the track that summed up my depression was “Country Feedback”. The track is slow and quiet, but Michael Stipe tosses out the phrase “fuck off” at the midpoint of the song with conviction. I was pissed off at having a broken heart but also sad by the implications of who broke it.

Exhibit D: Haruki Murakami, Hear the Wind Sing

![[Haruki Murakmi - Hear the Wind Sing] [Haruki Murakmi - Hear the Wind Sing]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/HearTheWindSingHarukiMu164_f-212x300.jpg) No, Hear the Wind Sing is not an album. It’s a novel. A Haruki Murakami novel, to be exact.

No, Hear the Wind Sing is not an album. It’s a novel. A Haruki Murakami novel, to be exact.

But it was a novel that served as the basis for an electronic song I wrote hoping to convince a guy I had a crush on to sing it. He couldn’t find the time to do it.

It had been a year since I returned from New York City, and I still wasn’t ready to accept the obvious direction of my sexual orientation. So something like writing a song hoping to get a guy I liked to sing it was just a totally rational thing for someone in my state of mind to do.

It took another 13 years before I transposed it to my own range, recorded it and sang it myself with much assistance by pitch-correction software.

Exhibit E: Emmylou Harris, Wrecking Ball

Emmylou Harris’ label directed its press efforts for her 1995 album Wrecking Ball to colleges and independent music outlets instead of country radio because it was her “weird album”. I snagged a promo of the album and fell in love with it.

The arrival of Wrecking Ball happened at the same time I wrote articles about National Coming Out Day, which resulted in my own. The two events are indelibly entwined. But I can’t think of a better album to serve as a soundtrack for that change.

It’s a dark, brooding album but also beautiful. I was still intimidated by the process of coming out, so I can’t say I look back on it as bright and joyous. I had a lot of work to do introspectively, and Wrecking Ball reflected that.

The album pretty much transformed Harris’ career, reaching a new audience as the old one moved on. It was certainly my pivot point as well.

Tags: emmylou harris, gay influence, midnight oil, murakami haruki, r.e.m., sting

![[The author, Sept. 1996]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/orlando_11_1996_02_cropped-228x300.jpg) Oct. 11 is National Coming Out Day, and this year marks the 20th anniversary of my own coming out. It’s not a coincidence. In fact, I set myself up for it.

Oct. 11 is National Coming Out Day, and this year marks the 20th anniversary of my own coming out. It’s not a coincidence. In fact, I set myself up for it.

I was features editor of my college newspaper in 1995 and taking a news writing class at the same time. My professors encouraged me to publish whatever I did for class in the paper. So I assigned myself a story about National Coming Out Day.

It was something of a personal dare.

Five years previous, I fell in love with my best friend in high school, a guy who couldn’t reciprocate. I was still nursing that broken heart when I went to New York City on an exchange program from 1992 to 1993.

A gay guy who was also participating in the program noticed my behavior, particularly toward a mutual straight friend, and explained to me what I was going through. I was not ready to listen to him.

So I pretty much lived in a haze when I returned from New York City to continue my studies in Honolulu. At that point, I pretty much assumed anyone for whom I felt a crush couldn’t possibly return my feelings. I made the same assumption about a guy in the music program who resembled my high school friend.

That brings us to the weeks before Oct. 11, 1995.

I asked a fellow music student if she could reach out to people who wouldn’t mind being interviewed for my article. One of the people who replied was that guy from the music program.

After the article went to press, I met up with him and told him my story. He pointed me to the counseling services on campus, and by the end of that year, I had told select members of my immediate family.

Twenty years on and … well, my dating life has been a total wash.

But I can’t imagine the last two decades carrying the psychic baggage of remaining in the closet. Even if my lifestyle doesn’t reflect how gay (white) men live today, I like having the option to participate. (Even though I’m not white.)

So I’ll be spending this next month commemorating this anniversary by writing about the music and musicians tied to this event and the history leading up to it. At the very least, my Duran Duran fandom will finally be explained.

Tags: gay influence

![[Steve Grand - All-American Boy]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/SteveGrandAllAmericanBoy126630_f-300x300.jpg)

I should know better than to like All-American Boy, the debut album by Steve Grand.

It’s the kind of over-compressed pop music that baits rockist former-record store employees to gnash their teeth and sneer. Even more rankling is the target audience for Grand’s big choruses and butch guitars — young gays with hot bodies very much like himself. If I were ungenerous, I’d call it “twink rock”.

But I can’t help think All-American Boy is also one of the most important albums I’ve encountered this year.

That’s right. Important.

Musically, All-American Boy hits all the radio-friendly cues. The guitars get louder when they ought to get louder. The piano gets plaintive when it ought to get plaintive. This album would not give Revolver any sleepless nights.

But lyrically, Grand sings love songs to other men, in a language these men would understand. That’s remarkable but still not the big deal. No, it’s part of a bigger deal.

The landscape for gay musicians has grown large enough for Steve Grand to record a pop album with a wall of guitars, for Jónsi to sing in Hopelandish in a stratospheric falsetto, for Ty Herndon to give country music some bonafide homosexual beefcacke, for Nico Muhly to light a fire under the classical music establishment’s ass and for Ed Droste to bore the fuck out of everyone within listening distance.

A decade ago, I lamented about how gay musicians couldn’t do rock. Throw together the words “gay” and “music” in the same sentence, it would invariably mean “dance music”, with “theater music” close behind. The only band with any amount of visibility at the dawn of the aughts was Pansy Division. Sure, there was Rufus Wainwright, but he’s more Elton John than Rob Halford.

Of course, the aughts were smack dab in the middle of the W. Bush administration. Gay people were embraced on the metropolitan coasts, but the big red swath in the middle of the country meant visibility held risks. Republicans put gay marriage bans on state ballots to ensure voter turnout among its base, and it fucking worked.

Music by gay musicians couldn’t escape the ghetto of the dance floor — or the folk guitar, as most “gay rock” seemed to be labeled back then — because it was still a cultural liability.

Oddly enough, the passage of Proposition 8 in California on the night Barack Obama was elected for his first term as president marked the shift in opinion. It was the victory that shouldn’t have been, and it galvanized allies to put deeds behind intentions.

It took a while before the victories started piling up — the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell; the decision striking down the Defense of Marriage Act — but once in place, that liability started to lose its teeth.

Members of metal bands such as Torche and Gaythiest would make Halford less of an anomaly. Adam Lambert gave American Idol its last bonafide star before The Voice gobbled up its viewing audience. Frank Ocean and Sam Smith went so far as to win Grammy Awards.

Country singer Chely Wright weathered a lot of crap for her coming out, but it opened up the door for Herndon and Billy Gilman to follow. It’s worth noting these revelations arrived after their biggest hits were behind them. The country music audience still has a lot of catching up to do.

Steve Grand is the latest beneficiary of this shift, and he’s taken it further by recording what could have been a very plain album with all the usual paeans boys sing to girls. Instead, he’s singing those paeans to other boys, and his age group isn’t batting an eye.

But Grand is part of a larger spectrum of music by gay artists, one that expands as visibility and acceptance become more commonplace. He doesn’t have to work in a ghetto. He can find an audience performing music in a style of his choosing without compromising his identity.

Tags: gay influence

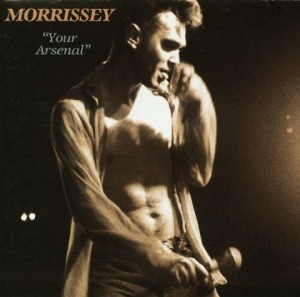

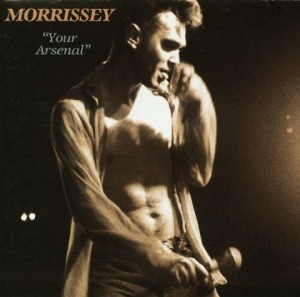

It’s a simple enough album cover: Morrissey in profile, holding a microphone in one hand, a taunting, silly expression on his face. His shirt is open, the lights of the stage casting strategic shadows across his bare chest.

Morrissey doesn’t have an Adonis physique, not like that show-off Sting on the back cover of the “Love is the Seventh Wave” 7-inch. Rather, he is lanky in a way that defies conventional appeal. He’s someone’s type, and it just so happens to be me.

But I wouldn’t have said as much in 1992, when Your Arsenal was first released.

For two semesters from fall 1992 to spring 1993, I lived in New York City. Tower Records was at its height, and the location on Broadway and W. 4th St. in the East Village was a regular destination for me on pretty much any day of the week.

Entire rows of endcaps in Tower brimmed with longboxes of Your Arsenal. I couldn’t take my eyes off of it.

Which sucked because I was deep in the closet, nursing a broken heart.

Morrissey’s physique reminded me of a high school friend, on whom I developed the harshest of crushes. The disapproval of my family would have been withering had I revealed my attraction to either Morrissey or my friend.

So I would gaze at those endcaps, “browsing” as it were, but also compelled by the sight of Morrissey’s revealing shirt. His pose was both seductive and stand-offish.

A few months later, New York City would be bombarded by large billboards of Mark Wahlberg, a burgeoning actor transitioning from a failed rap career. His modeling of Calvin Klein underwear marked the turning point. Many young gay men ensconced with those bus stop posters to put Mr. Wahlberg on their walls.

And still at the time I didn’t have the bravery to be one of them.

But Morrissey, Mark Wahlberg, the diversity of New York City … they started to chip away at the Catholic upbringing against which I only started to rebel.

My turning point happened three years later when I met a guy who I thought was cute. He turned out to be gay, and while dating was never in the cards, I found comfort in the thought a guy for whom I felt attraction could very well feel it as well.

It was not the paradigm I encountered when I fell for my high school friend.

Morrissey was a distant memory by that point. My attention had turned to avant-garde and international music, minimalist composers and jazz improvisers inspired by John Cage. Oh, and Duran Duran was having a pretty good resurgence at that point as well.

I would go on to explore more music and not think about Morrissey or Your Arsenal unless I just happened to encounter the album while seeking something else.

And it never fails to draw my eyes. And it never fails to transport me back to New York City, 1992.

I didn’t get on board with Morrissey in earnest till the mid-2000s. I finally sated my curiosity about the Smiths and understood. I even checked out Morrissey’s latter-day solo work, but Your Arsenal still wasn’t a priority.

I knew I would only want to get it for the cover.

Streaming services have been a great boon for making informed purchasing decisions, and when the “Definitive Master” of Your Arsenal was announced, I did my research. Yes, it is indeed a good album, and yes, I determined I would indeed own it.

Now, the question: do I also get it on vinyl?

Tags: gay influence, morrissey

![[Dead or Alive - Youthquake]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/DeadorAliveYouthquake19158047_f-300x300.jpg)

![[Duran Duran, 1983] [Duran Duran, 1983]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/duran_duran_us_1983.jpg)

![[Sting - Love Is the Seventh Wave] [Sting - Love Is the Seventh Wave]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Sting-Love_Is_The_Seventh_Wave_New_Mix-Back--296x300.jpg) The back cover of this single had Sting posing without a shirt, and I couldn’t tear my eyes away. My household toed the homophobic line because my parents were devoutly Catholic and my brother and sisters weren’t old enough to come to their conclusions. So I would sneak peeks at this image surreptitiously, not exploring why I was so powerfully drawn to it.

The back cover of this single had Sting posing without a shirt, and I couldn’t tear my eyes away. My household toed the homophobic line because my parents were devoutly Catholic and my brother and sisters weren’t old enough to come to their conclusions. So I would sneak peeks at this image surreptitiously, not exploring why I was so powerfully drawn to it.![[Haruki Murakmi - Hear the Wind Sing] [Haruki Murakmi - Hear the Wind Sing]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/HearTheWindSingHarukiMu164_f-212x300.jpg) No, Hear the Wind Sing is not an album. It’s a novel. A Haruki Murakami novel, to be exact.

No, Hear the Wind Sing is not an album. It’s a novel. A Haruki Murakami novel, to be exact.![[The author, Sept. 1996]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/orlando_11_1996_02_cropped-228x300.jpg)

![[Steve Grand - All-American Boy]](https://musicwhore.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/SteveGrandAllAmericanBoy126630_f-300x300.jpg)